Happy number

A happy number is defined by the following process. Starting with any positive integer, replace the number by the sum of the squares of its digits, and repeat the process until the number equals 1 (where it will stay), or it loops endlessly in a cycle which does not include 1. Those numbers for which this process ends in 1 are happy numbers, while those that do not end in 1 are unhappy numbers (or sad numbers[1]).

Contents |

Overview

More formally, given a number  , define a sequence

, define a sequence  ,

,  , ... where

, ... where  is the sum of the squares of the digits of

is the sum of the squares of the digits of  . Then n is happy if and only if there exists i such that

. Then n is happy if and only if there exists i such that  .

.

If a number is happy, then all members of its sequence are happy; if a number is unhappy, all members of its sequence are unhappy.

For example, 19 is happy, as the associated sequence is:

- 12 + 92 = 82

- 82 + 22 = 68

- 62 + 82 = 100

- 12 + 02 + 02 = 1.

The happy numbers below 500 are:

- 1, 7, 10, 13, 19, 23, 28, 31, 32, 44, 49, 68, 70, 79, 82, 86, 91, 94, 97, 100, 103, 109, 129, 130, 133, 139, 167, 176, 188, 190, 192, 193, 203, 208, 219, 226, 230, 236, 239, 262, 263, 280, 291, 293, 301, 302, 310, 313, 319, 320, 326, 329, 331, 338, 356, 362, 365, 367, 368, 376, 379, 383, 386, 391, 392, 397, 404, 409, 440, 446, 464, 469, 478, 487, 490, 496 (sequence A007770 in OEIS).

The happiness of a number is preserved by rearranging the digits, and by inserting or removing any number of zeros anywhere in the number.

The unique combinations of above (the rest are just rearrangements and/or insertions of zero digits):

- 1, 7, 13, 19, 23, 28, 44, 49, 68, 79, 129, 133, 139, 167, 188, 226, 236, 239, 338, 356, 367, 368, 379, 446, 469, 478, 556, 566, 888, 899.(sequence A124095 in OEIS).

Sequence behavior

If n is not happy, then its sequence does not go to 1. What happens instead is that it ends up in the cycle

- 4, 16, 37, 58, 89, 145, 42, 20, 4, ...

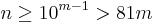

To see this fact, first note that if n has m digits, then the sum of the squares of its digits is at most  , or

, or  .

.

For  and above,

and above,

so any number over 1000 gets smaller under this process and in particular becomes a number with strictly fewer digits. Once we are under 1000, the number for which the sum of squares of digits is largest is 999, and the result is 3 times 81, that is, 243.

- In the range 100 to 243, the number 199 produces the largest next value, of 163.

- In the range 100 to 163, the number 159 produces the largest next value, of 107.

- In the range 100 to 107, the number 107 produces the largest next value, of 50.

Considering more precisely the intervals [244,999], [164,243], [108,163] and [100,107], we see that every number above 99 gets strictly smaller under this process. Thus, no matter what number we start with, we eventually drop below 100. An exhaustive search then shows that every number in the interval [1,99] either is happy or goes to the above cycle.

The above work produces the interesting result that no positive integer other than 1 is the sum of the squares of its own digits, since any such number would be a fixed point of the described process.

There are infinitely many happy numbers and infinitely many unhappy numbers. For example, if one wonders if any number will produce 14,308, say, the quick response is to write down the digit "1" 14,308 times and you have created such a number. In fact, infinitely many such numbers exist since zeros can be inserted at will.

The first pair of consecutive happy numbers is 31, 32.[2] The first set of triplets is 1880, 1881, and 1882.[3]

An interesting question is to wonder about the density of happy numbers. In the interval ![[1,10^{122}]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/32b136e342286b0b5b6a118f90208794.png) , 15.5% (to three significant figures) are happy.(sequence A068571 in OEIS)

, 15.5% (to three significant figures) are happy.(sequence A068571 in OEIS)

Happy primes

A happy prime is a number that is both happy and prime. The happy primes below 500 are

7, 13, 19, 23, 31, 79, 97, 103, 109, 139, 167, 193, 239, 263, 293, 313, 331, 367, 379, 383, 397, 409, 487 (sequence A035497 in OEIS).

All numbers, and therefore all primes, of the form 10n + 3 and 10n + 9 for n greater than 0 are Happy (This of course does not mean that these are the only happy primes, as evidenced by the sequence above). To see this, note that

- All such numbers will have at least 2 digits;

- The first digit will always be 1 due to the 10n

- The last digit will always be either 3 or 9.

- Any other digits will always be 0 (and therefore will not contribute to the sum of squares of the digits).

- The sequence for adding 3 is: 12 + 32 = 10 → 12 = 1

- The sequence for adding 9 is: 12 + 92 = 82 → 82 + 22 = 64 + 4 = 68 → 62 + 82 = 36 + 64 = 100 -> 1

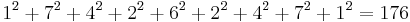

The palindromic prime 10150006 + 7426247×1075,000 + 1 is also a happy prime with 150,007 digits because the many 0's do not contribute to the sum of squared digits, and  , which is a happy number. Paul Jobling discovered the prime in 2005.[4]

, which is a happy number. Paul Jobling discovered the prime in 2005.[4]

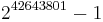

As of 2010[update], the largest known happy prime is  (Mersenne prime). Its decimal expansion has 12,837,064 digits.[5]

(Mersenne prime). Its decimal expansion has 12,837,064 digits.[5]

Special happy numbers

- 986,543,210 : Greatest happy number with no redundant digits

- 1,234,456,789 : Smallest zeroless pandigital happy number

- 10,234,456,789 : Smallest pandigital happy number

- 13,456,789,298,765,431 : Smallest zeroless pandigital palindromic happy number

- 1,034,567,892,987,654,301 : Smallest pandigital palindromic happy number

Happy pythagorean triplets

- All Pythagorean triplets with all integers happy and less than 10000

| ( 700, 3465, 3535) | ( 748, 8211, 8245) | ( 910, 8256, 8306) | ( 940, 2109, 2309) |

| ( 940, 4653, 4747) | (1092, 1881, 2175) | (1323, 4536, 4725) | (1527, 2036, 2545) |

| (1785, 3392, 3833) | (1900, 1995, 2755) | (1995, 4788, 5187) | (2715, 3620, 4525) |

| (2751, 8360, 8801) | (2784, 6440, 7016) | (3132, 7245, 7893) | (3135, 7524, 8151) |

| (3290, 7896, 8554) | (3367, 3456, 4825) | (3680, 5313, 6463) | (4284, 5313, 6825) |

| (4633, 5544, 7225) | (5178, 6904, 8630) | (5286, 7048, 8810) | (5445, 6308, 8333) |

| (5712, 7084, 9100) | (6528, 7480, 9928) |

Happy numbers in other bases

The definition of happy numbers depends on the decimal (i.e., base 10) representation of the numbers. The definition can be extended to other bases.

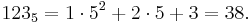

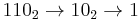

To represent numbers in other bases, we may use a subscript to the right to indicate the base. For instance,  represents the number 4, and

represents the number 4, and

Then, it is easy to see that there are happy numbers in every base. For instance, the numbers

are all happy, for any base b.

By a similar argument to the one above for decimal happy numbers, unhappy numbers in base b lead to cycles of numbers less than  . If

. If  , then the sum of the squares of the base-b digits of n is less than or equal to

, then the sum of the squares of the base-b digits of n is less than or equal to

which can be shown to be less than  . This shows that once the sequence reaches a number less than

. This shows that once the sequence reaches a number less than  , it stays below

, it stays below  , and hence must cycle or reach 1.

, and hence must cycle or reach 1.

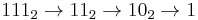

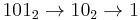

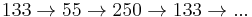

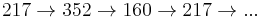

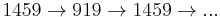

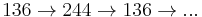

In base 2, all numbers are happy. All binary numbers larger than 10002 decay into a value equal to or less than 10002, and all such values are happy: The following four sequences contain all numbers less than  :

:

Since all sequences end in 1, we conclude that all numbers are happy in base 2. This makes base 2 a happy base.

The only known happy bases are 2 and 4. There are no others less than 500,000,000.[6]

Cubing the digits rather than squaring

An interesting extension to the Happy Numbers problem is to find the sum of the cubes of the digits rather than the sum of the squares of the digits. For example, working in base 10, 1579 is happy, since:

- 13+53+73+93=1+125+343+729=1198

- 13+13+93+83=1+1+729+512=1243

- 13+23+43+33=1+8+64+27=100

- 13+03+03=1

In the same way that when summing the squares of the digits (and working in base 10) each number above 243(=3*81) produces a number which is strictly smaller, when summing the cubes of the digits each number above 2916(=4*729) produces a number which is strictly smaller.

By conducting an exhaustive search of [1,2916] one finds that for summing the cubes of digits base 10 there are happy numbers and eight different types of unhappy number:

those that eventually reach  which perpetually produces itself.

which perpetually produces itself.

those that eventually reach  which perpetually produces itself.

which perpetually produces itself.

those that eventually reach the loop

those that eventually reach  which perpetually produces itself.

which perpetually produces itself.

those that eventually reach the loop

those that eventually reach  which perpetually produces itself.

which perpetually produces itself.

those that eventually reach the loop

those that eventually reach the loop

Starting with the happy numbers and then following with the unhappy numbers in the order given above, the density of each type of number in the interval [1,2916] is 1.54%, 28.4%, 34.7%, 5.73%, 17.4%, 4.60%, 3.60%, 2.67% and 1.34% (all to 3 significant figures).

Intriguingly, the second type of unhappy number includes all multiples of three . This fact can be proved by the exhaustive search up to 2916 and noting that a number is a multiple of three if and only if the sum of digits is a multiple of three if and only if the sum of its cubed digits are a multiple of three. By similar reasoning, all happy numbers of this type must have a remainder of 1 when dividing by 3.

One interesting result which comes from the above work is that the only positive whole numbers which are the sum of the cubes of their digits are 1, 153, 370, 371 and 407.

Origin

The origin of happy numbers is not clear. Happy numbers were brought to the attention of Reg Allenby (a British author and Senior Lecturer in pure mathematics at Leeds University) by his daughter, who had learned of them at school. However, they "may have originated in Russia" (Guy 2004:§E34).

Popular culture

In the 2007 Doctor Who episode "42", a sequence of happy primes (313, 331, 367, 379) is used as a code for unlocking a sealed door on a spaceship about to collide with a sun. When the Doctor learns that nobody on the spaceship besides himself has heard of happy numbers, he asks, "Don't they teach recreational mathematics anymore?"

Programming example

The examples below apply the 'happy' process described in the definition of happy given at the top of this article, repeatedly; after each time, they check for both halt conditions: reaching 1, and repeating a number. Everything else is book-keeping (for example, the Python example precomputes the squares of all 10 digits.

SQUARE = dict([(c, int(c) ** 2) for c in "0123456789"]) def is_happy(n): s = set() while (n > 1) and (n not in s): s.add(n) n = sum(SQUARE[d] for d in str(n)) return n == 1

References

- ^ "Sad Number". Wolfram Research, Inc.. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SadNumber.html. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ "Lower of pair of consecutive happy numbers". Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://oeis.org/A035502. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ "First of triples of consecutive happy numbers". Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://oeis.org/A072494. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ The Prime Database: 10^150006+7426247*10^75000+1

- ^ Prime Pages entry for 242643801 - 1

- ^ Sloane's A161872 : Smallest unhappy number in base n. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ Happy Number Rosetta Code

Additional resources

- Walter Schneider, Mathews: Happy Numbers.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Happy Number" from MathWorld.

- Happy Numbers at The Math Forum.

- Guy, Richard (2004). Unsolved Problems in Number Theory (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-20860-7